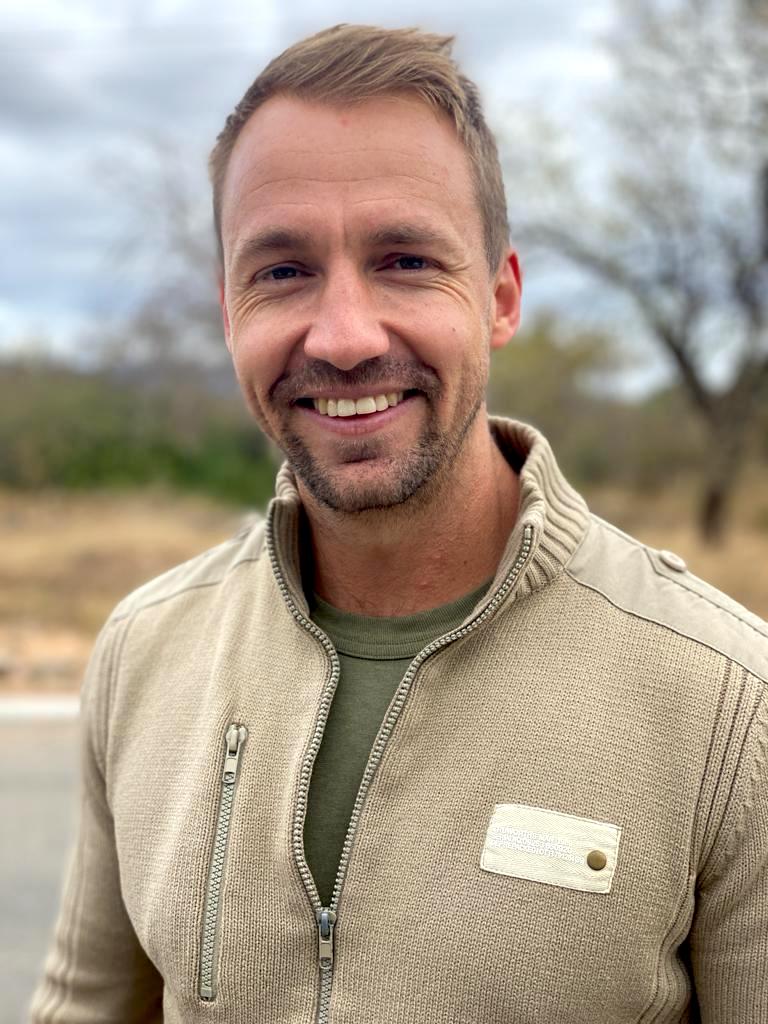

GCC’s Founder Matt Lindenberg shares the amazing journey that took him from South Africa to the United States and back again, meeting outstanding people along the way that led him to start his own non-profit. Through his work at GCC he is starting to create an important shift in local children’s relationship to the wildlife around them.

Has conservation always interested you?

Wildlife has always had my full attention. The pivotal moment in my early childhood was when my parents took me for a day trip to visit friends at Sabi Sands Reserve, which borders the world-famous Kruger National Park. We were quite an active family; always hiking, cycling, canoeing and spending time outdoors. On this particular excursion, we were visiting a friend’s lodge having lunch, when two of the field rangers offered to take me with them for a short walk. These weren’t the usual field guides that often interact with tourists, but rather field rangers that the public rarely sees. They offered to have me tag along for the afternoon and we saw lion tracks, hippos, and a Mozambique spitting cobra. They made me walk past the snake with my eyes closed. To this day, I don’t know if they were teasing me or genuinely looking out for my safety, but the experience stayed with me and inspired me at a deep level. I hope our work at GCC can have the same impact on children today.

As a teenager, did this passion for conversation continue?

I had rather troubled teenage years. There was a bus crash that really impacted the tourism industry and our guest house and my parents’ business folded. We lost the house, my parents got divorced and my sister and I went to the US with our Dad. The years passed and I didn’t know what I wanted to do. I was into snowboarding and tennis. During high school, I got a scholarship to play tennis. I was in the top 100 in Southern California, but an injury suddenly put an end to that. I also loved flying and wanted to be a fighter pilot so I decided to study mechanical engineering to pursue a flying career, only to find out that I was color blind and would never be able to fly professionally. So, I quit university and decided to return to South Africa to visit my mom. We spent a few days in the bush where we came across some of Africa’s most iconic species like lions, cheetah and elephants. It was during this trip that I became reacquainted with my deepest passion; wildlife and conservation. A few weeks later, I said goodbye to the US, packed up all my belongings and turned in my US green card. The next week I enrolled in a field guide training course at the Southern African Wildlife College.

What was your first conservation job?

During my training at the Wildlife College, a family friend offered me a field guiding job at a 5-star lodge. However, upon qualification, I called the family friend only to be answered by his secretary with the unapologetic fact that the position had been filled. So here I was in South Africa, after leaving everything in the US behind me, with a guiding qualification and no employment to speak of. It was horrible. Around a month later, I was going to join my grandmother for our usual mediation class and it was canceled at the last minute. So, she said “let’s go gambling and have a night out!” So off we went to the casino at Cesar’s Palace at Johannesburg’s OR Tambo airport. I remember sitting there with my grandmother when I saw Theresa Sowry, the CEO of the Southern African Wildlife College, walk through the immense crowd of people. I ran over to her to say hi and she asked how the job was going. I explained that it didn’t work out and that I was unemployed and she said: “On Monday, come and work with me as a volunteer.” Theresa was a role model for me and this was the moment when everything changed.

What happened next?

I worked for the Wildlife College for the next six years, first as a volunteer, and then guiding guests and teaching English to children in the surrounding communities. This experience was invaluable as I got an insight into how things work in the local schools and communities. Concurrently, I enrolled at the University of South Africa, and studied in the evenings after long days in the bush. I received a BSc in Zoology and Geography which qualified me to assist in training reserve managers, guides and field rangers. I eventually managed to earn my conservation pilots license, which was one of my most rewarding experiences to date. Those were my formative years. I learned so much. From there, I was offered a Master’s degree scholarship from Grand Valley State University, Michigan. My research was conducted with the Cheetah Conservation Fund in Namibia, and I investigated the introduction of seven captive-raised cheetahs back onto Namibian farmlands.

What inspired you to start your own conservation organization?

My inspiration comes from two places. Firstly, in 2008, I was in the dining hall of the Wildlife College when I saw this Zulu man, Martin Mthembu, one of the most respected ranger trainers, sitting alone. People were constantly going up to him to say hello and pay their respects. I knew this man was someone special, and so I sheepishly asked if I could join him for lunch. Martin was to become my mentor, taking me under his wing. He saved my life three times, twice from lions and once from a black mamba. During his career, he trained over 15,000 rangers throughout Africa and spoke nine languages fluently. He would take frustrated youth and inspire them to create a better life for themselves. He was a shining star where shining stars didn’t exist. He influenced so many people and rangers from all walks of life, and there were countless amazing stories about him. On the 2nd August, 2014, he died tragically in a car accident and I was devastated. I wanted to be a voice and continue his legacy so it wouldn’t be buried with him. I couldn’t stop thinking about all those unpolished gems who had not yet met Martin.

The second inspiration came from a very different collection of experiences. I started to notice that the people working in conservation were either foreign, wealthy and/or privileged individuals who were paying large amounts of money to volunteer and “make a difference”. And while these individuals certainly have an important role to play, local people could never afford to pay these amounts of money for exclusive conservation experiences. It was wrong on so many levels. Local youth were not seeing the animals and they were lacking empathy for them as a result. Sometimes, people are quick to blame others, without rarely putting themselves in their shoes. Thinking from the perspective of an impoverished and uneducated individual; if I had no future, living in a place with poor infrastructure, little food, and my parents were sick, I would do whatever I could to survive. And if the only chance of survival means snaring an impala or killing a rhino, then what would you do? Unless we involve the local people who live next to wildlife, we will never win this war.

You have produced a documentary called Rhino Man; can you tell us about this project?

Rhino Man was the first project I started. The idea was to create a short video to tell the world about the rangers. When we started, very few people were talking about the rangers and about how they were sacrificing their lives to protect the rhinos. It is an important story to tell. The making of this film has been really hard and we still haven’t finished the final product. But at the end of the day, the mission was to honor Martin and tell the ranger story. If it hadn’t been for John Jurko II, one of the film’s directors, the story wouldn’t have evolved in the way it has. There have been so many amazing people that have supported this film since its inception, and I cannot wait for this message to get out into the world!

How has GCC evolved since the Rhino Man project?

During filming, we were always supporting the rangers with backpacks, watches, boots, all kinds of tactical equipment really, which enabled us to build an amazing relationship with the rangers and the management of the Timbavati Private Nature Reserve. One day when we were filming in 2017, I noticed that one of the most senior rangers, Anton, was looking really down. I asked him what was up and we sat down with his right-hand man and he shared his concerns saying “How long can we hold the line, buying time? What is the world doing? We work such long hours, for little pay, in dangerous conditions, and this isn’t going to fix the problem.” He shared that he was almost 50 years old and how local children are becoming further and further disconnected from nature and wildlife. Even his own kids were not seeing wildlife very often. He shared with me that this concern was even greater than rhino poaching because who would replace him and his rangers? Will the next generation care more or less about these wild spaces, and would they be more corruptible when bribed? Anton asked GCC to focus more on the youth and to ensure than the next generation of community conservationists cared, had empathy, and wanted wildlife to exist. This is the origin story of the Future Rangers Program.

How does the Future Rangers project work?

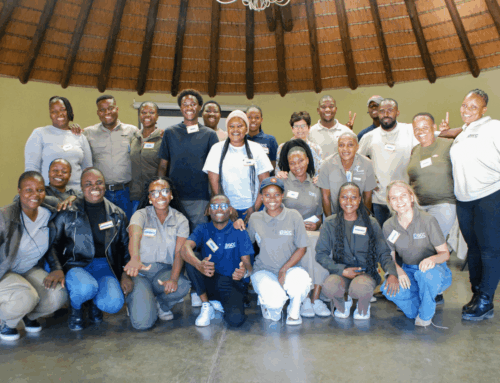

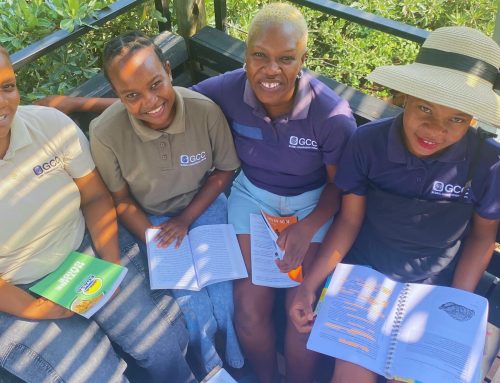

Over the last two years, we have been working with four primary schools, next to the Kruger National Park. We partner with a local facilitator who works with each school. The schools teach children from the ages of five to 13 and the facilitators are qualified environmental educators. They are at school every day, and every single kid has one lesson per week. But we want to make sure that the children are not only hearing about it but seeing it too, so we organize game drives, have guest lecturers visit the schools, and encourage extra-curricular conservation activities.

What are you working on right now?

This week is quite exciting as we are starting to work in four high schools. We want to follow the students we have taught in primary school and ensure this environmental program and support continues as the children move through their high school years. High schools are the forgotten land when it comes to environmental education, and this is where we prepare the next generation of leaders entering the job market. To address a gap in the education material, we have built a curriculum with our partners (Africa foundation), which is aligned with the South African government’s standards for education. We now reach over 4,000 children collectively every week. Moving forward, our goal is to scale this program by bringing on more and more implementation partners, who see the value in investing in youth surrounding conservation areas.

What are you most excited about?

I think the four new high schools get me really excited. In our area, this approach has not been done before at this scale and quality. We also have new partnerships with the Africa Foundation and the Southern African Wildlife College. The further along I get on this journey, the more I realize the immense value of partnerships and working together. At the end of the day, we are all on the same team, and embracing this reality is what is required to truly move mountains.

However, it is sometimes the little things that make me excited. At Christmas, we took our team out for an end of year celebration and they all got dressed up and were so proud and we went out to a fancy restaurant. I dropped off one of the facilitators, who is an amazing teacher, home after the party and she told me that she wouldn’t want to be doing anything else than what she is doing right now and I realized that touching one person’s life in a meaningful way is the best reward. Seeing that you’ve made a difference to someone else’s life, that is just strength and pure joy for me.