We do it for love and not money. But without any money at all, well then we find ourselves in very interesting times. — Ashwell Glasson —

So what does a global pandemic and conservation have to do with each other? Many things. Personally, we might be thinking about the impact of COVID-19 on our health, our job security and personal freedoms. Some of us have taken those freedoms for granted, for a long time. In conservation, we generally work with limited funds and make up for it with passion, zeal and personal interest. If I asked a room filled with conservationists, most people in that room would likely agree with me. We do it for love and not money. But without any money at all, well then we find ourselves in very interesting times.

Today, the conservation sector is intimately connected with the broader economy of South Africa and many other tourism-centric countries including Botswana, Zambia, Namibia, Zimbabwe. Many of the countries I have mentioned rely on international tourism to sustain their conservation areas, with each US dollar, Euro, Pound, and other international currencies helping to pay critical salaries of field rangers, trackers, field guides, conservation managers and workers from local communities. Whether building game fences, repairing roads, educating school children through environmental education programmes; the tourism dollar helps sustain it all. Every trip to a national park, reserve, and lodge in Africa likely has a positive impact on species survival (not just the lions, leopards, and cheetahs), sustaining rural families, employment opportunities, putting children through school and helping build homes. Formal conservation and protected areas are often located in rural areas with high levels of poverty and lack of infrastructure that many of us take for granted. Without a thriving tourism economy, the entrenched poverty can be a recruiting ground for desperation and criminality.

One of the more recent crises that have emerged in these areas has been the illegal wildlife trade. This trade is synonymous with commercial poaching, industrial-style wildlife farming and transnational criminal networks that perpetuate growing violence and criminalize vulnerable communities and individuals. We know that these syndicates create local systems of communication, patronage and sadly corruption—moving poached animals, horns, tusks, firearms, people and more across borders. Rachel Kleinfeld, a leading researcher in the study of violence, has estimated that more people are dying because of violence within societies than at war and the most significant proportion of it, is from organized crime. With the stabilizing force of tourism being shut down indefinitely in these communities, who will be tasked with holding the conservation line?

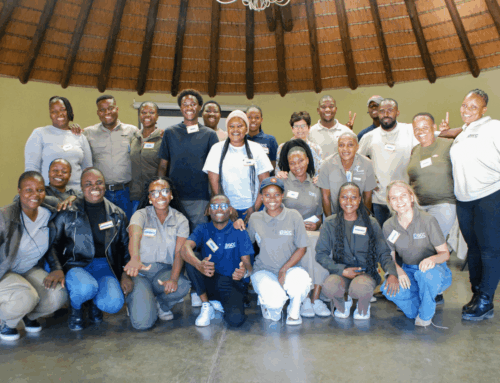

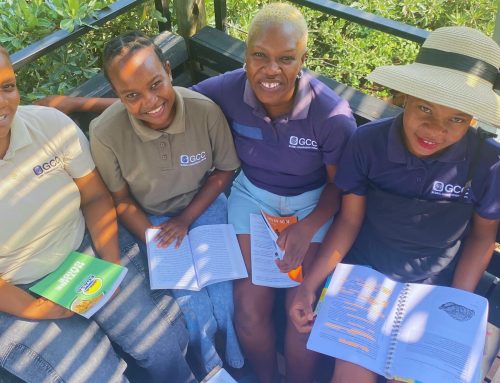

Here we enter the realm of the silent guardian – the Field Ranger. Unlike regular police and military forces around the world, most field rangers lack adequate resources and funding. They are often at the back of the queue when needing equipment, training, and support. The unwanted arrival of COVID-19 has now put field rangers under increasingly heavy risks and added stresses. Firstly, COVID-19 has heavily reduced tourism income for many parks and reserves due to lockdowns and travel restrictions. This means less financial resources for reserves and ultimately an impact on conservation activities, including the essential services of field rangers. Practically, this might mean layoffs or salary cuts.

In South Africa and some of the countries in the region, COVID-19 has redirected the police to focus on human movement and other mitigation actions. This means less dedicated time to collaborate with rangers and management to investigate wildlife crime, processing new cases, and follow-up court action. Thus, the deterrence action by law enforcement becomes lessened for commercial poachers, which increases the risk of incursions and potential wildlife poaching.

The local restrictions on certain goods, training, and services also put limits on what field rangers and conservationists can do to sustain their reserves. The costs for non-medical items unrelated to COVID-19 goes up, as transport and logistics are far more restricted. Things like GPS’s, smartphones, field kits and similar are hard to come by.

And probably the hardest blow to field rangers is throughout this national lockdown, their inability to see or visit their families. When South Africa issued the national lockdown on the 26th March, 2020, rangers were forced to make a difficult decision; hold the line inside the reserve, or remain with their families until the lockdown ended. There could be no middle ground, as the transmission of COVID into reserves could compromise the health of an entire security division, leaving a reserve and its wildlife unguarded. The majority of rangers within the greater Kruger Park area remained true to their commitment to conserving these wild places, while their families remain vulnerable during these times. With the lockdown already having been extended once, rangers can only hope that their loved ones remain safe, healthy and able to source adequate food, water, and medical support if required.

In a country blessed with such rich fauna, flora, biodiversity and natural beauty, it would be wise to remember the “thin green line” during this time. Without rangers, tourism, employment, and all the intrinsic beauty nature holds, might not be there after this storm. So next time you visit a national park or protected area, be sure to sincerely thank the individuals who held the line, for us all.