Kate Vannelli, GCC’s Program Director, talks about the state of conservation at the end of 2020, the implications of COVID-19, lessons learned this year and the next steps for conservation going forward.

2020 was a year for the books, in the worst possible way (although all the dogs that were adopted this year would beg to differ). I’m sure we’ll be relaying the trials and tribulations associated with this year for many generations to come, although there’s a chance that this might be hinting at the ‘new normal’, as we increasingly suffer the effects of ecosystems being degraded by human activity. However, instead of bracing myself with ‘the worst is yet to come’ mindset, I’ve chosen, along with many others in the field of conservation, to see an opportunity to act upon a warning bell that has been ringing for years.

This year, the world changed drastically with the emergence of COVID-19, a virus sprung from humans’ exploitative relationship with the natural world. Although it was a year filled with bad news, 2020 wasn’t all bad. In the absence of bustling people (otherwise known as the ‘anthropause’), wildlife everywhere was able to relax for a little while. Deer were seen wandering previously busy streets in broad daylight, and the world even witnessed a few pumas exploring temporarily empty-seeming cities. Whales had a welcome break from underwater noise pollution and scientists had a very unique opportunity to study how many wildlife species act in the absence of humans. And humans came through for wildlife in more ways than one! In a historic decision, Colorado voters opted to restore gray wolves to their western mountains by 2024. Carnivore reintroduction has historically never been up to voters, so this was a monumental moment in re-wilding efforts. And on the topic of voting, with the election of Joe Biden, the US is slated to rejoin the Paris Climate Accord, meaning the country will commit to an updated climate and emissions reduction target. This is good news, as the US is the second largest greenhouse gas producer in the world.

However, the events that have unfolded this year have highlighted some of the systemic issues linked to our exploitative relationship with the natural world. This has given us a unique chance to reflect on the underlying causes of these issues, and why going back to ‘business as usual’ in conservation is simply not an option.

An important example of this is that local communities are bearing the brunt of the pandemic effects. The communities on which conservation depends have been historically marginalized and excluded from conservation interventions, and are now disproportionally suffering the effects of the pandemic. A close reliance on natural resources has led to food shortages, loss of livelihoods and lack of personal protective equipment: these situations are especially affecting women. Additionally, without funding from the tourism sector, many anti-poaching efforts have gone underfunded, leaving wildlife vulnerable to poaching. With the food shortages and loss of livelihoods, these increased socio-economic divides are linked to an increase in poaching, and have added strain to the relationship between conservation and communities in many areas.

Further, environmental issues are notoriously underfunded in the philanthropic sector, and the pandemic has fully exposed our conservation funding crisis. While governments have responded to pandemic impacts in other sectors of the economy with bailouts, conservation has received no such funding, and with ecotourism and other traditional routes of funding conservation ceasing, this has uncovered the fragile state of conservation funding.

More than anything, this year has caused a shift: a shift in priorities, a shift in our actions, and hopefully, a shift in urgency. This has opened up an opportunity to not only address the cause of COVID-19, but to also repair our relationship with the natural world, which has the potential to positively affect many of the global issues we are facing, especially within conservation. While the pandemic exposed weaknesses within our approach to conservation (a dependency on tourism and external funding, low government priority, neocolonialism, operating independent of other sectors, etc.), it also highlighted opportunities where conservation can pivot and improve its approach.

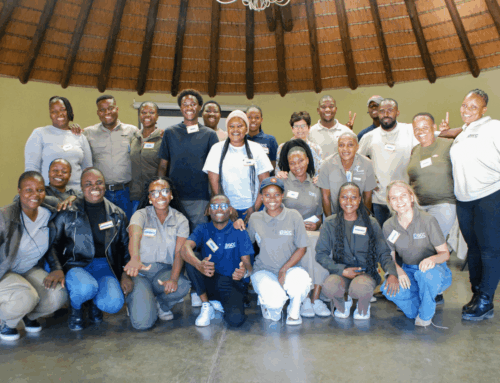

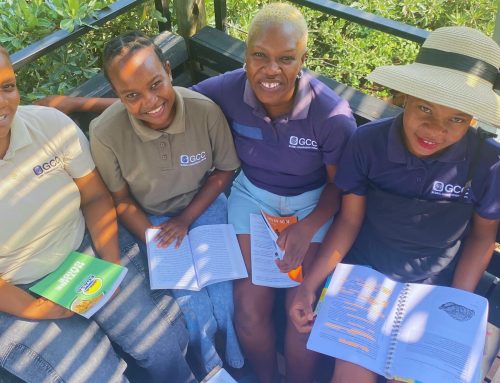

This year has opened the conversation around a complete reboot to the way conservation is approached. It has highlighted the dire need to move towards a system that addresses the root cause of the issues we are facing, rather than utilizing reactionary, and often insufficient solutions. In particular, the global movement against racism has sparked many conversations about power and privilege in the conservation space, prompting conservationists to reflect on the importance of prioritizing local people and local leadership within the communities living alongside wildlife in Africa. Alongside the environmental justice movement, conservation should be working towards a more equitable system of intersectional environmentalism by centering the frontline communities as equal leaders in conservation decision-making. This is becoming increasingly recognized as the way forward, which is a major shift and a big win for potential conservation successes down the line.

There has also been a shift in thinking around how conservation is funded and prioritized, especially since protected areas are proving to be a vital buffer against zoonotic diseases (like COVID-19) while also having the potential to boost economic growth and resilience. With the increasingly obvious and tangible value presented in protecting nature, this has emphasized the importance of developing more sustainable and diversified ways to earn revenue from nature, with several case studies standing out as a divergence from ‘business as usual’; which is exactly what conservation needs. With this shift comes the potential to leverage the increased support for conservation from the global community by facilitating more buy-in from local and international policy-makers, business leaders, and philanthropists in order to address conservations’ underlying major challenges, including poverty, equitable education, mismanagement and colonial approaches to conservation. There is a major opportunity to collaborate across sectors in order to address the fragmenting landscapes, exploitation of wildlife, pollution and general disregard of our reliance on nature, all of which, if not addressed, will lead to future pandemics. This is a problem that requires preventative action, and it is not too late to take that action.

2020 has provided a very ‘in-our-face’ call to reconcile the damage that humans have done, both to our ecosystems and to ourselves. It has given us a pause to take a hard look at ourselves and our relationship with the natural world, and the realizations have been sobering. We have more problems on our hands than the number of times the word ‘unprecedented’ was used in email communications this year (hint… it’s a LOT). However, we also have a very clear picture of how we need to proceed. If we can work together in conservation to diversify livelihoods, prioritize indigenous voices and needs, create stronger collaborations, and prioritize and finance conservation on a global scale, we’ve got a really solid start. It begins with an understanding that our survival is inextricably linked to a thriving natural world, and we must take this opportunity that 2020 has presented and do better.